■Rich and Poor Trout Streams■

肥沃な鱒川と不毛な鱒川

Ed Jahn fishing Manchester Brook in August low water. I took him there only when I found he was leaving town.

LET ME TELL YOU about a couple of my favorite trout streams. One is Armstrong’s Spring Creek, on the O’Hair Ranch in the Paradise Valley of the Yellowstone River in Montana. You stop at the ranch house and pay an obscenely low fee (fifteen dollars in April, thirty during the summer) to fish one of the world’s richest little trout streams, in both insect life and trout population. You can wade across its transparent riffles and barely get your ankles wet, yet every day of the year a trout over twenty inches is a possibility on a small Pheasant Tail nymph or Blue-Winged Olive dry.

私のお気に入りの鱒川を2・3紹介しよう。ひとつはモンタナ州のイエローストーン川のパラダイス・バレーにあるオヘア牧場のアームストロング・スプリングクリークだ。牧場に立ち寄り、信じられないくらいの低料金(4月は15ドル、夏は30ドル)を払うと、昆虫と鱒の生息数で世界で最も豊富な小鱒川の1つで釣ることができる。透明な瀬を歩いても足首が濡れる程度で、さらに小さなキジ科のニンフやブルーウィングオリーブドライで、20インチを超える鱒が毎日釣れる。

The other stream flows right through my town; let’s just call it Manchester Brook (loose lips crowd small streams). Manchester Brook flows with about the same volume of water as Armstrong’s Spring Creek, and it is about as wide, yet the largest fish I have taken in fourteen years of fishing it was just shy of thirteen inches. Where every pool in Armstrong’s holds scores of rainbows and browns over fifteen inches long, with many more small fish as well, a decent pool in Manchester Brook will offer one brook trout of ten inches, maybe an eleven-inch brown, and a half-dozen more trout of both species that, laid end-to-end, might total a couple of Armstrong’s average fish.

もう1つの小川は、私の町のすぐ近くを流れていて、ここでは、マンチェスターブルックと呼ぶことにしよう(ルーズ・リップの群れの小川)。マンチェスターブルックはアームストロング・スプリングクリークをほぼ同じ水量で、幅も同じで、14年間の釣行で釣り上げた最大の魚は13インチに僅かに及ばないものであった。アームストロングのどのプールにも15インチ以上のニジマスやブラウンが何匹もいて、さらに多くの小魚がいるのに対して、マンチェスターブルックのまともなプールには10インチのブルックが1匹、11インチのブラウンが1匹、更に両種の鱒が6匹ほどいて、端から端まで並べても、アームストロングの平均魚が数匹いるようなものだ。

In Manchester Brook you can blind-fish with a Hare’s Ear nymph or the buggy dry fly of your choice: Humpies, Irresistibles, Haystacks, and Ausable Wulffs will catch trout all season long, any time of day. Yet if you try the same tactics in Armstrong’s, you’re guaranteed to draw a blank. In Armstrong’s you have to go two or three fly sizes smaller, and the successful flies will be of a different type from those you can get away with in Manchester Brook. If you try to prospect or blind-fish with a dry fly in Armstrong’s, you’ll spend much of your day looking at an unmolested fly. In general trout in rich streams won’t come for a dry fly if there is nothing of interest hatching, while trout in infertile streams will come to a dry almost all day long, even if there are no insects on the water’s surface. The difference between the two is geology, and nothing more.

マンチェスターブルックではヘアーズエアー・ニンフや好みのバギードライフライで、ブラインド・フィッシングできます。ハンピー、イレジスティブル、ヘイスタック、オーサブルウルフなど、シーズン中いつでも鱒をキャッチできます。でもアームストロングで同じ戦術を試してみても、空振りに終わることは間違いない。アームストロングではフライを2〜3サイズ小さくする必要があり、成功するフライはマンチェスターブルックで使えるものは異なるタイプになる。アームストロングでドライフライで、プロスペクトやブラインドフィッシングをしようとすると、一日中、邪魔にならないフライを眺めて過ごすことになります。普通、豊かな川の鱒は関心のある虫の羽化がなければ、ドライフライを食わないが、不毛な川の鱒は、たとえ水面に虫がいなくても、ほとんど一日中ドライを取りに来る。両者の違いは地質学なものであり、それ以外のものは何もない。

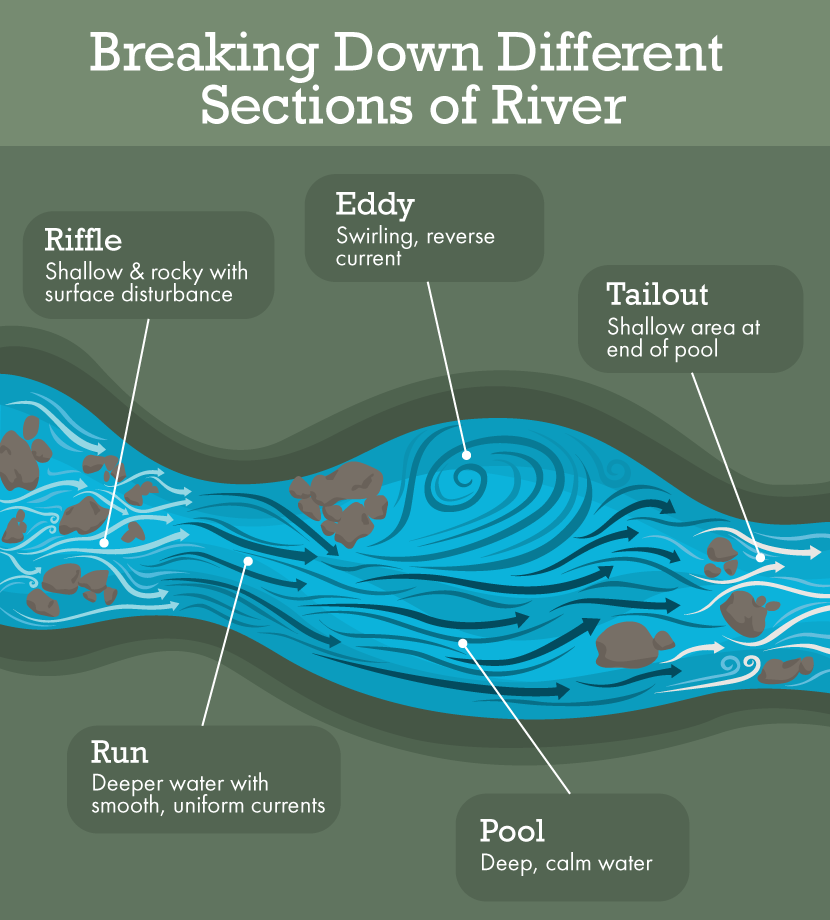

Geology determines the entire character of a trout stream. A glance at the surrounding terrain can tell you how big the trout will grow, how much food is available to them, and how they will be distributed in the stream; it also helps you predict their feeding behavior and even what flies will work. Trout streams are made from water and rock, or rock particles like sand and silt. The chemical composition of the water comes from compounds leached from surrounding rock. These compounds encourage or discourage the growth of algae, diatoms, insects, crustaceans, and rooted aquatic plants, which form the food chain that supports a trout population. Surrounding vegetation also contributes to the food chain, as aquatic invertebrates feed on dead and decaying shore plants, but even this part of the chain is dependent on the geology of the stream’s banks. The slope of a stream, which dictates its riffleto-pool ratio, is a function of bedrock. The types of rock determine the size of the particles in the bed of the river, which in turn fixes not only the number and type of aquatic invertebrates but also the number of places trout have to live.

地質が鱒の川全体の性格を決定している。周囲の地形を見れば、鱒がどのくらいの大きさに成長し、どのくらいの餌があるか、流れの中にどのように生息しているかが分かる。また、鱒の摂餌行動やどの種類のフライが良いか、を予測するのに役に立つ。鱒の川は、水と岩、あるいは砂やシルトなどの岩石の粒子からできている。化学組成は周囲の岩石から溶出した化合物に由来している。これらの化合物は、藻類(algae)、珪藻類(けいそうるい、diatom、川石に付着する藻)、昆虫、甲殻類(crustancean)、根の生えた水生植物などの成長を促進したり抑制したりし、鱒の個体数を支える食物連鎖(food chain)を形成しています。水生無脊椎動物(aquatic invertebrate)は枯れたり腐ったりした岸辺の食物を食べるので、周囲の植物も食物連鎖貢献しますが、この部分は河岸のち質に左右される。渓流の傾斜は瀬と淵の比率を決定するのは岩盤である。岩盤の種類によって川底の粒子の大きさが決まり、それによって水生無脊椎動物の数や種類が決まるだけでなく、鱒が生息する場所の数も決まります。

Armstrong's Spring Creek. It has about he same volume of flow as Manchester Brook in April, and probably ten times the trout population. John Holt photo.

If you intend to fish only to rising fish during hatches, geology and a knowledge of stream reading are unimportant. You need only sample the drift to find out what flies will work, and you know where the fish are because you can see them feeding. But when you prospect without the benefit of hatches, you need other clues to help you select flies and find fish. The relative richness of a river, which you can usually determine with a few minutes of observation, is one of the most important clues.

Manchester Brook begins high in the Green Mountain massif, which is composed of Precambrian gneiss and quartzite. The metamorphic rocks that make up its bed offer little enrichment because these rocks are mostly insoluble silica. The water is much the same as rainwater runoff — on the acidic side with little of the dissolved calcium found in richer streams. The stony, thin, acidic soil also encourages the growth of conifers, especially hemlock, which, as the early settlers of New England found, is a source of tannic acid. The water has the tea-stained look of tannin, which comes directly from the hemlocks and from humic acid formed in bogs by the decomposition of organic matter.

虫が羽化するときに、ライズする魚だけ釣るつもりなら、地質や流れを読む知識は重要ではない。どんなフライが効果的か、漂流物をサンプルすればいいし、魚がどこにいるかは、エサを食べているところを見えるのだから。でも、ハッチの恩恵にあずからずに、釣りを期待する場合、フライの選択や魚を見つけるのに役に立つ他の手がかりが必要です。川の相対的豊かさは、数分間の観測で普通判断できるが、これは最も重要な手がかりの1つだ。

マンチェスターブルックは先カンブリア時代(Precambrian)の片麻岩(へんまがん)と珪岩からなるグリーンマウンテン山塊(massif)の高台から始まる。変成岩(metamorphic rocks)の大半は不溶性のシリカであるので、川底の変成岩は水質をほとんど変化させない。水質は雨水の流出水とほとんど同じで、酸性側で、豊かな河川で見られる溶存カルシウムはほとんどありません。石が多くて、薄く、酸性の土壌は、針葉樹、特にニューイングランドの初期の入植者(settlers)が発見したように、タンニン酸の供給源であるヘムロック(樹木、毒ニンジン)の成長を促進する。このタンニンはヘムロックと、沼地で有機物の分解でできる腐酸性から直接発生するもので、水は紅茶のような色をしている。

Now if you look at a geological map of the Paradise Valley, just north of Yellowstone Park where Armstrong’s Spring Creek flows, you’ll see a band of Paleozoic Madison limestone and dolomite. This band crosses the Yellowstone River valley just south of Livingston, exactly where the three famous spring creeks — Armstrong’s, DePuy’s (actually the lower end of the same spring source as Armstrong’s), and Nelson’s — flow out of the ground and into the Yellowstone. Elsewhere in Paradise Valley, where the Yellowstone flows through basement rock of gneiss, granite, and schist, the tributaries are stony, with wide channels that indicate frequent spring floods. In midsummer the stream channels are often dry, or nearly so. But where the Yellowstone cuts through the ten-mile-wide strip of limestone, the character of the feeder streams changes dramatically. The soft limestone bedrock is dissolved by the acidity in rainwater and groundwater, and pressure on the water table from the high mountains on either side of the river valley squirts water up through holes in the wormy bedrock, forcing water to the surface in artesian springs and making the feeder streams run bank-full throughout the season.

それでアームストロング・スプリング・クリークが流れるイエローストーン公園のすぐ北にあるパラダイスバレーの地質図を見ると、古生代(paleozic)のマディソン石灰岩(limestone)とドロマイトの帯が見えます。この帯はリビングストンのすぐ南で、イエローストーン川の谷を横断しており、まさにアームストロング、デピューズ(実際はアームストロングズと同じ源泉の下端)、そしてネルソンの3つの有名なスプリングクリークが地中から流れ出してイエローストーンに注ぐ場所です。イエローストンが片麻岩(gneiss)、花崗岩(granite)、片岩(schist)の基盤岩を流れるパラダイス・バレーの他の場所では、支流は石だらけで、春の洪水が頻繁に起きることを示す広い流路を持っている。

One immediately apparent difference between the two streams is stability. Manchester Brook rises and falls and rises again from rainfall to rainfall. Snow melting in the spring in the mountains above raises the water level to the edges of the banks and beyond, while during a dry summer the brook shrinks to a tenth of its former volume, only to rise to early spring levels with a summer cloudburst. On the other hand Armstrong’s is monotonously constant, and when I fished it during the unprecedented dry summer of the Yellowstone Park fires, I could see no appreciable difference in flow from wet late Aprils during years of heavy runoff. This difference in stability partly explains the difference in growth rates of trout, and it also helps you figure out which flies and techniques to use in the two streams. Armstrong’s never floods, so the concomitant loss of food supply, heavy mortality of young trout, and expenditure of a lot of energy by adult trout evading floodwaters don’t occur. In Manchester Brook heavy mortality of both the food supply and the trout population is a yearly occurrence. Where Manchester Brook’s water temperatures range from the mid-30s in winter to the mid70s in summer, Armstrong’s seldom waver from the 50s even in the dead of winter, because the water comes directly from the ground, and groundwater reflects the mean temperature of its latitude. Trout don’t feed and grow when the water temperature gets below 45 or above 70, so the trout in Armstrong’s are eating and putting on inches in mid-January, when the fish in Manchester Brook are in suspended animation.

この2つの流れの違いですぐに分かることは、安定性です。マンチェスター・ブルックは雨が降っては落ち、また降っては上がる。春になると上の山の雪解け水で水位が土手際までまたはド手際を越えて上昇し、乾燥の夏には小川の水量は以前の1/10まで減り、夏の豪雨で春先の水位に戻るという具合だ。一方、アームストロング川の水量は一定で、イエローストーン公園の火災で未曾有の(unprecedented)乾燥した夏に釣行した際には、流出量の多い4月下旬の水量と大きな差は感じなかった。この安定性の違いは、鱒の成長速度の違いを部分的に説明していて、また2つの川でどのフライや技術を使うべきかを考える助けにもなっている。アームストロングでは洪水は起こらないので、これによるエサの喪失、若い鱒の大量死、洪水を回避する鱒の成魚の大量エネルギー消費は起きない。しかし、マンチェスターブルックでは、エサの喪失と個体数の過密による大量死が毎年起きています。マンチェスターブルックの水温は冬の30度台から夏の70度台まであるが、アームストロングは真冬でも50度台から殆ど変わらない。これは、水が地面から直接湧き出しており、地下水はその井戸の平均温度を反映しているからだ。水温が45度(7℃)以下、あるいは70度(21℃)以上になると、鱒は餌を食べなくなり、成長しなくなるため、マンチェスターブルックの魚が仮死状態(suspended animation)にある1月下旬でも、アームストロングの鱒はエサを食べて何インチも太って(put on weight)いる。

The Ausable in New York state is relatively infertile, and as a result most of its trout are small.

There are other factors that make streams running through limestone richer than those running through quartzite, sandstone, or gneiss. Even streams that are not spring-fed but that run through limestone or other calcareous rock are much richer than those that run through mostly silicate rock. Penn’s Creek in central Pennsylvania is a good example. It is hardly a model of stability — in fact, every time I have tried to fish this famous river, it has been chocolate brown and over its banks. Yet even though it does not have the rich, clear, weedy character of a spring creek, because it flows through limestone bedrock it is much richer in insect and crustacean life than similar-appearing, silicate-bedded streams.

石灰岩(limestone)を流れる川が、石英岩(quartzite)、砂岩(sandstone)、gneiss(片麻岩)を流れる川よりも豊かなのは、他にも要因がある。湧水地(spring-fed)でなくても、石灰岩や石灰質(calcareous)の岩石を流れる川は、ほとんど珪酸塩(silicate)の岩石を流れる川よりはるかに豊かだ。ペンシルベニア州中央部のペンズ・クリークはその好例だ。この川は安定性のモデルとは言い難い。実際、この有名な川で釣ろうとするたびに、川はチョコレート色に濁り、水量は土手を越えてしまうことがある。しかし、この川は石灰岩の岩盤を流れているため、スプリング・クリークのような豊かで、透明で、雑草(weedy)のない特徴をもっていないにも関わらず、同じように見える珪酸塩(silicate-bedded)で覆われた川よりも昆虫や甲殻類の生息数がずっと豊かである。

Given smaller seasonal stability and runoff pattern, a “hard” water stream will be richer than one with “soft” water. Any rock composed primarily of calcium or magnesium carbonate will leach into water, thereby “hardening” the water and giving you a richer trout stream. The most important such rocks for our purposes are limestone, composed primarily of calcium carbonate, dolomite, or calcium magnesium carbonate, and marble, composed of metamorphosed limestone or dolomite. Many empirical studies have proven that trout grow faster and behave differently in hard water streams. A Pennsylvania study of three soft water and three hard water streams with similar drainage patterns showed that trout’s growth rate was directly related to specific conductivity, which is a measure of dissolved calcium and magnesium salts in the water. Another study, in England, proved that limestone stream trout have a much lower seasonal variation in diet than those from soft water streams, and they grow faster as a result.

季節的な安定性と流出パターンが小さいと、「硬水」の川は「軟水」の川よりも豊かな水質を持つことになる。炭酸(carbonate)カルシウムと炭酸マグネシウムを主成分とする岩石は水に溶けだし(leach into)、それによって水が硬くなり、より豊かな鱒川を作ることができる。そのような岩石で最も重要なものは、炭酸カルシウム、ドロマイト、炭酸カルシウムマグネシウムを主成分とする石灰岩と、変成石灰岩またはドロマイトからなる大理石だ。たくさんの実証的研究により、硬水の川では鱒の成長は速く、挙動が異なることが証明されている。ペンシルベニア州の研究では、排水パターンの似た軟水と硬水の3つの小川で、鱒の成長速度が比伝導度(水中のカルシウムとマグネシウムの溶解度の尺度)に直接関係していることが示された。また、英国の研究では石灰質の渓流の鱒は軟水質の渓流の鱒に比べて、エサの季節変動が非常に小さく、その結果成長が早いことが証明された。

Before you think we’re going off on a tangent far removed from learning to catch trout when there are no hatches, let’s take a look at how rich streams differ from less fertile ones, and at some practical ideas that surface as a result. Assume for the time being that soft water streams are not as rich as hard water streams — you’ll learn how you can eyeball the relative richness of trout streams.

ハッチの無いときにマスを釣る方法とかけ離れた話(we're going off tangent )だと思われる前に、豊かな川と肥沃でない川がどのように違うか、そしてその結果として現れる実用的なアイデアについて見てみよう。とりあえず(for the time being)、軟水の川は硬水の川のように豊かでないと仮定して、鱒川の相対的な豊かさを目測で判断する方法を学びましょう。

Predicting a Trout’s Feeding Habits

鱒の摂餌を予想すること

Rich trout streams have a steady, constant food supply. At the height of the richness scale are spring creeks, which differ little throughout the world. The Le Tort in Pennsylvania, Armstrong’s in Montana, and the Test in England have virtually the same food supply as spring creeks in Argentina and New Zealand. Twelve months a year the fish feed on midge pupae, small Blue-Winged Olive nymphs, scuds, and sow bugs. I grew up fishing a small spring creek in upstate New York, and the fly box I used when fishing this stream has served me well on spring creeks elsewhere. Although, if I fish a spring creek in midsummer, I add a couple of ant and beetle patterns, for the most part I can use the same half-dozen patterns in November or April.

豊かな鱒川は安定したエサを供給している。豊かさの頂点にあるのがスプリング・クリークであり、これは世界中どこでも変わりません。ペンシルベニアのル・トート川、モンタナのアームストロング川、異グリスのテスト川は、アルゼンチンやニュージーランドのスプリング・クリークとほど同じエサを供給しています。1年のうち12ヶ月間、魚はミッジピューパ、小型のブルーウィング・オリーブニンフ、スカッド、ダンゴムシ(sow bugs)などをエサにしている。私はニューヨーク州北部の小さなスプリングクリークで育ったので、この小川で釣ったときのフライボックスは他の場所のスプリングクリークでも役立っている(serve me well)。でも、真夏にスプリングクリークを釣るときは、アリやカブトムシのパターンをいくつか加えますが、大抵は11月と4月でも同じ半ダースのパターンを使うことができます。

A "collector" on the lower Henry's Fork in Idaho, similar to those on the Missouri.

Medium-rich streams like the Beaverkill, the Madison, or the Battenkill lack the constant water temperature and water level of spring creeks, but they still offer trout an almost endless buffet. The difference is that the kind of food changes throughout the season, and a nymph that trout climb all over in late April may be ignored in July. If I planned to fish a medium-rich trout stream like the Deschutes in Oregon, a river that I’ve never seen but hope to someday, I would not have the same confidence in the contents of my fly box, and I’d have to read up on the river, hire a guide, or stop in to a local fly shop before I chose my flies.

Beaverkill, Madison, Battenkillなどの中くらい豊かな川ではスプリングクリークのように水温や水位は一定ではありません。それでも、鱒にはほぼ無限のビュッフェを与えられている。ただ、餌の種類は季節によって変わり、4月下旬に鱒が寄ってきたニンフも、7月には無視されることもある。私がオレゴンのデシューツ川のような中くらいに豊かな鱒川で釣りをしようと思ったら、まだ見たことがなく、いつか見たいと思ってた川だけど、フライボックスの中身は自身が持てず、フライを選ぶ前にその川について調べたり、ガイドを雇ったり、地元のフライショップに立ち寄ったりしなければならないだろう。

Relatively infertile streams offer a small and inconsistent food supply. Think of the upland brooks or mountain streams you have fished — the bouldery kind common in New Hampshire, North Carolina, Vermont, Montana, or California. Or imagine one of those boggy, tea-colored streams punctuated with beaver ponds that run through the lowlands of Maine, Michigan, and Wisconsin. Infertile streams are usually smaller — larger rivers run through wider valleys and pick up nutrients from rich bottomland sediments. If a larger river runs through rocky canyons, however, it too may offer a sparse food supply. Examples would be the Gallatin in Montana, the Ausable in the Adirondacks, or the Penobscot in Maine. It can be argued that the Ausable or the Gallatin offers good hatches for the fisherman, but the day-to-day food supply, the stuff that puts inches around a trout’s waist, is not as abundant as in rivers that flow through more fertile valleys.

比較的肥沃でない渓流はエサの供給が少なく不安定でもある。ニューハンプシャー、ノースカロライナ、バーモント、モンタナ、カルフォルニアなどで見られる、岩だらけの高地の小川や渓流で釣りをしたことのある人は考えてみてください。あるいは、メイン州、ミシガン、ウィスコンシン州の低地を流れる、ビーバーの池が点在する沼地のような紅茶色の小川を思い浮かべてください。肥沃でない小川は普通は小さい川です。大きな川は広い谷を流れ、豊かな底質からの栄養分を吸収します。大きな川が岩だらけの渓谷を流れているなら、そこにはまばらな(sparse)エサしか供給されていないことがある。例えば、モンタナ州のギャラティン川、アディロンダック山脈のオーサブル川、メイン州のペノブスコット川などがそうだ。オーサブル川やギャランティン川は釣り人にとって良いハッチを提供しているが、日々の食料供給、つまり鱒のウエストを何インチも太らせるようなものは、より肥沃な谷を流れる川ほど豊富でない、ということが言える(it can be argued that)でしょう。

The bad news is that you’ll have trouble predicting what kinds of food are prevalent in an unfamiliar infertile stream. The good news is you probably won’t have to. Further good news is that the flies you can get away with will be larger. Trout in infertile rivers don’t have the luxury of being selective, because they don’t see enough of anyone insect to get picky about which one they choose. Either they eat every piece of food that looks remotely edible or they starve. In most infertile rivers the quantity of aquatic insect larvae available to the fish by midsummer is insignificant, and they depend on terrestrial insects that fall into the water for a great part of their food. Since they never see many of the same kind of aquatic insects, and the terrestrials they feed on are a stew of all shapes, sizes, and colors (and we’ve seen in the last chapter that, all else being equal, trout prefer to eat the largest morsel of food available), all you have to do is turn over a few rocks or shake the bushes and decide what is the largest edible insect they are likely to recognize.

悪いことは、不慣れな不毛の渓流でどんな食べ物が支配的か予測することは困難であろう。良いニュースは、おそらく君がする必要がないことです。更に良い点は、使用できるフライが大きくなることだ。不毛の川の鱒は、どの昆虫を選ぶか選り好みするほど多くの昆虫を見ないので、選り好みする余裕はありません。食べられると思われるものを片っ端から食べるか、餓死(starve)するかのどちらかです。多くの不毛の川では、真夏に魚が食べる水生昆虫の量はわずかで、エサの大部分を水中に落ちている陸生昆虫に頼っている。同じ種類の水生昆虫はあまり見かけないし、餌となる陸生昆虫は形、大きさ、色もバラバラで(前章で、他の条件が同じなら鱒は大きなエサを好むことが分かった)、岩をひっくり返したり、茂みを揺らしたりして、鱒が認識しそうな一番大きな食用昆虫は何かと考えるだけでよいのである。

In more fertile rivers you have to pay greater attention to what’s on the menu. The trout are used to seeing multiple foods at any given time, and although they are not usually selective to a given species of insect, most of their food falls into specific parameters of size, shape, and color. If you go outside of that realm, you won’t draw as many strikes. Here the largest available food item might be rare enough that trout don’t recognize it. In the Battenkill, for example, most of the nymphs are small, skinny, and brownish olive-dull. If you turn over enough rocks, though, you’ll sometimes find a couple of those giant black stoneflies that trout go crazy over in the Rocky Mountains. I have tried size 6 stonefly nymphs in the Battenkill year after year, with never even a touch. Not only do the trout not eat them, I bet if I could look underwater I’d see them bolting for cover when that ugly nymph rolls into the neighborhood.

肥沃な川では、メニューに何があるかにもっと注意を払わなければならない。鱒は常に複数の餌を見ることに慣れて(be used to )いて、通常、特定の種類の昆虫を選択することはないが、エサの殆どは、サイズ、形、色などの特定のパラメータに当てはまる。その領域から外れると、多くのストライク引き寄せることが出来ません。また、鱒が認識できないような大きなエサが稀にあります。例えば、バテンキルのニンフはほとんどが小さく、ヤセ型で、茶色がかったオリーブ色のくすんだ色(olive-dull)をしている。でも、十分な量の岩を裏返せば、ローッキーマウンテンで鱒が夢中になる大きな黒いストーンフライを2−3匹見つけることができるのです。私はバテンキルで毎年サイズ6のストーンフライを試してきているが、一度のアタリもない。鱒が食べないだけでなく、もし水中を見ることが出来たなら、その醜いニンフが近所に転がり込んだとき、鱒がカバーに逃げ込むのが見えたに違いありません。

I’ve found that in richer rivers, smaller flies are more effective. I’m not exactly sure why. Perhaps it’s because smaller insect life is more abundant, and the fish are more likely to take a fly that’s similar to what they’re eating, while the fish in an infertile stream grab almost anything that looks edible. On the Beaverkill in midJune, blind-fishing during the middle of the day when hatches were sparse, I once had to go down to a size 18 caddis to catch trout even in the riffles. Big Wulffs, variants, and other attractor flies didn’t even draw splashy refusals. I decided to explore a nearby tributary, which by the look of the water was nowhere near as rich as the Beaverkill. Tired of straining to see the tiny caddis, I put on a size 10 Ausable Wulff, more to enjoy watching the fly bouncing on the riffles than anything else. You know the rest of the story. In every pool there were a couple of trout eager to take the bushy fly as soon as it hit the water. This was less than a hundred yards from trout that wouldn’t even look at a fly larger than a 16. Since that day I’ve noticed that on rich streams like the Bighorn or the Battenkill, I seldom do well blind-fishing with a fly larger than size 16 (except for streamers and during grasshopper time). On small streams or on rivers like the Ausable or the Gallatin, for between-hatch periods I can get away with size 10 or 12 nymphs and dries — although during hatches of smaller flies I still use the tiny stuff.

豊かな川では、小型のフライが有効であることが分かった。その理由はよくわかりませんが、不毛な川では、魚は食べられそうなものは案でも手にするのに対して、豊かな川では小さな虫が豊富で、魚が食べているものと同じようなフライを食う可能性が高いからかもしれません。6月中旬にビーバーキルで、マッチがまばらな日中にブラインドフィッシングをしたとき、瀬の中でも鱒を釣るためにサイズ18のカディスに、サイズを小さくしなければならなかったこともある。大きなウルフやバリアント、その他のアトラクターフライでは、水飛沫を上げて拒否(draw splashy refusal)されることもあった。私は近くの支流を探ることにした。水の様子から、ビーバーキルのような豊かさはどこにもないよう(nowhere near)だった。小さなカディスを見るのに苦労した私は、サイズ10のオーサブルウォルフを装着し、それよりもなによりも、瀬の上で跳ねるフライを楽しむことにした。後はおわかりだろう。どのプールにも、bushy フライが着水するやいなや、それを食おうとする鱒が2・3匹いた。サイズ16以上の大きなフライには見向きもしないようなマスから、100ヤードも離れていない場所でのことだ。その日以来、ビッグホーンやバテンキルのような豊かな川では、サイズ16より大きなフライでブラインドフィッシングをすることはほとんどないことに気がついた(ストリーマーやバッタの時期は別です)。小川やオーサブル、ギャラティンなどの河川では、ハッチの合間には10番や12番のフライで十分でだが、小さいフライのハッチ時期は、やはり小さいものを使う。

One of the most important clues you can get from eyeballing the richness of a river is a sense of how the trout are distributed. When you don’t have the benefit of rising fish to tell you where they are, knowing where they should be saves you from fishing over unproductive water. There is nothing more frustrating than blindfishing a piece of water, wondering if there are any trout at all underneath your fly. When I fish a stream I have never seen before and start to doubt the presence of trout anywhere near my fly, my confidence erodes and I lose concentration. As a result I can get sloppy about what I’m doing. If you know that feeling too, read on for a confidence booster.

川の豊かさを目視することで得られる最も重要な手がかりの1つは、鱒の分布状況を把握することです。ライズしている魚がどこにいるか教えてくれない場合、魚がどこにいるべきかを知っていれば、非生産的な水の上を釣らずに済みます。フライの下に鱒がいるかどうか考えながら、ブラインドフィッシングするほど、イライラするものはない。一度も見たことの川で釣りをして、フライの近くに鱒がいるかどうか疑い始めると、だんだん自信がなくなり、集中力が途切れてしまう。その結果、自分のしていることが手抜きになってしまう。君がそういった感覚をお持ちなら、自信を取りもどうために、この生地を読んでみてください。

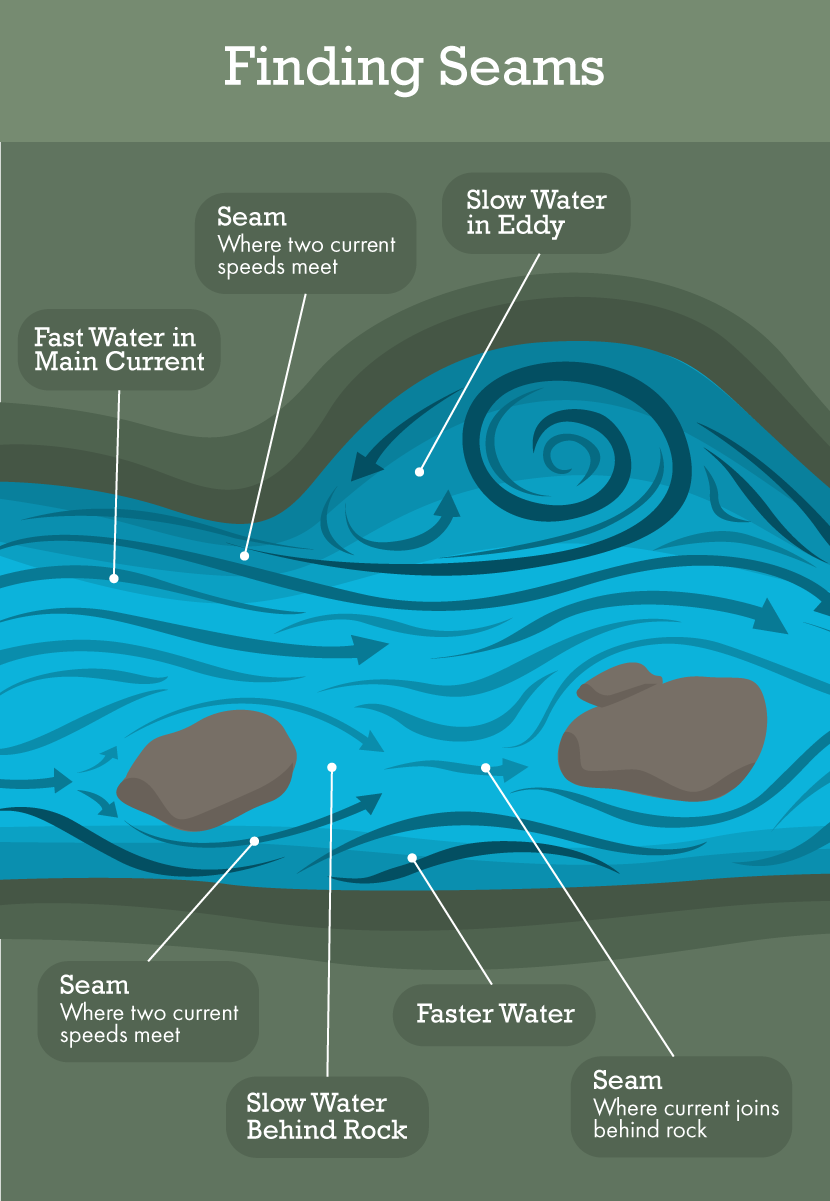

The first time I fished the Missouri River was a lesson in the value of fishing water I would have passed up on other rivers. The Missouri is a productive tailwater, and its currents carry a rich soup of insect life all the time. Paul Roos, who was guiding my wife Margot and me, kept talking about looking for “collectors.” At first I couldn’t figure out what he was talking about, but Paul has guided on the Missouri for over twenty years, so I kept my eyes open and my mouth shut. When Paul finally pointed out a collector, I realized he meant the slow, barely swirling backwaters along the bank and behind islands in the river, where trout waited to collect flies that had drifted out of the main current. The trout could lie just under the surface without expending much energy because the currents were nearly imperceptible. Paul used the term ‘collectors’ to describe both the places and the fish, and we soon found ourselves gazing with intense concentration at water we wouldn’t have given a second glance on other rivers. The Missouri is so rich fish can thrive on the extra food that peels off from the main current. I suspect that on the Missouri the bigger fish are found in the collectors: their energy expenditure is at a minimum, so they can grow bigger, faster.

ミズーリ川で初めて釣りをしたことは、他の川では見過ごされてしまうような水の価値について教えてくれるものだった。ミズーリ川は生産性の高いテールウォーターであり、その流れはいつも昆虫の豊かなスープを運んできます。妻のマーゴと私をガイドしてくれたポール・ルースは「コレクター」を探せとずーっと言っていた。最初何のことだがわからなかったが、ボールは20年以上ミズーリ川でガイドをしているので、私は目を見開き、口を噤んだままだった。ポールがようやくコレクターを指差したとき、それは川の岸辺や中島の背後にある、ゆっくりした、ほとんど渦をまかない逆流のことだと分かった。流れが殆どないので、鱒はエネルギーを使わずに水面下に潜むことができる。ポールはこの場所と魚のことを「コレクター」と呼んでいたが、他の革では見向きもしない(give a second glance)ような水を、私達はいつの間にか集中して見つめていた。ミズーリ川はとても豊かなので、魚は本流からはみ出した余分なエサで成長することができる。ミズーリ川では大きな魚はコレクターにいて、エネルギー消費量は最小なので、より速く、より大きく成長できる、と推測している。

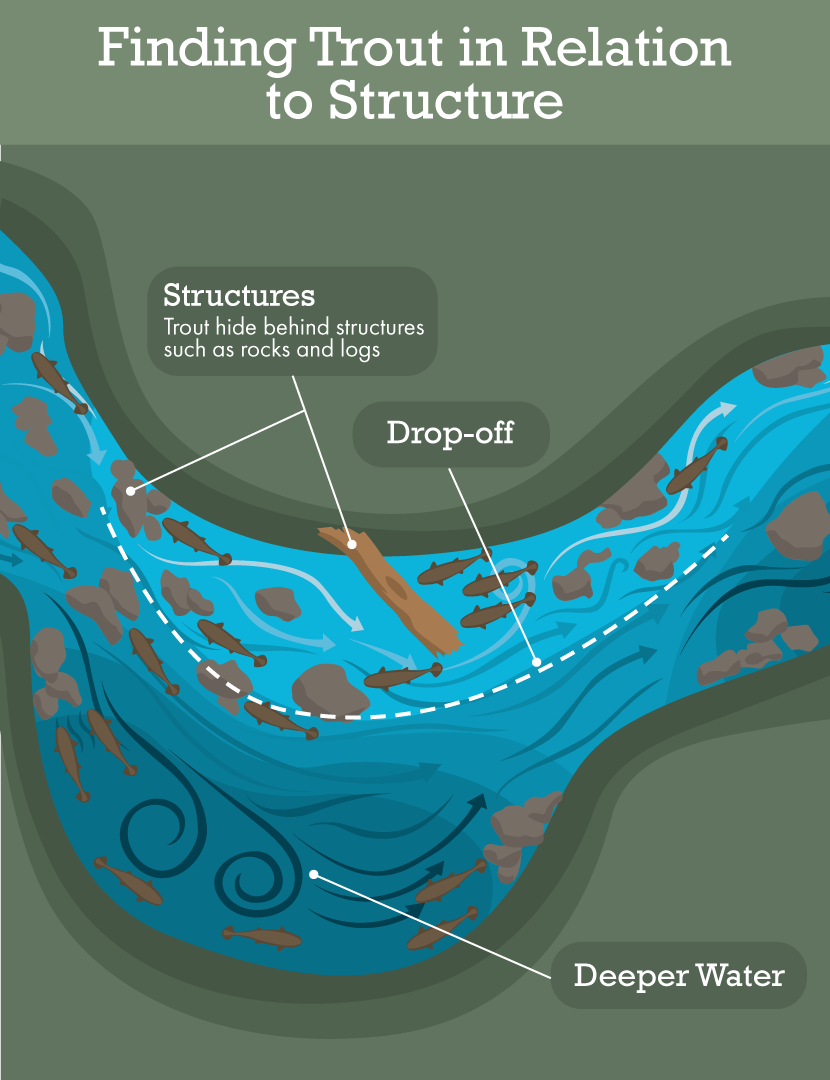

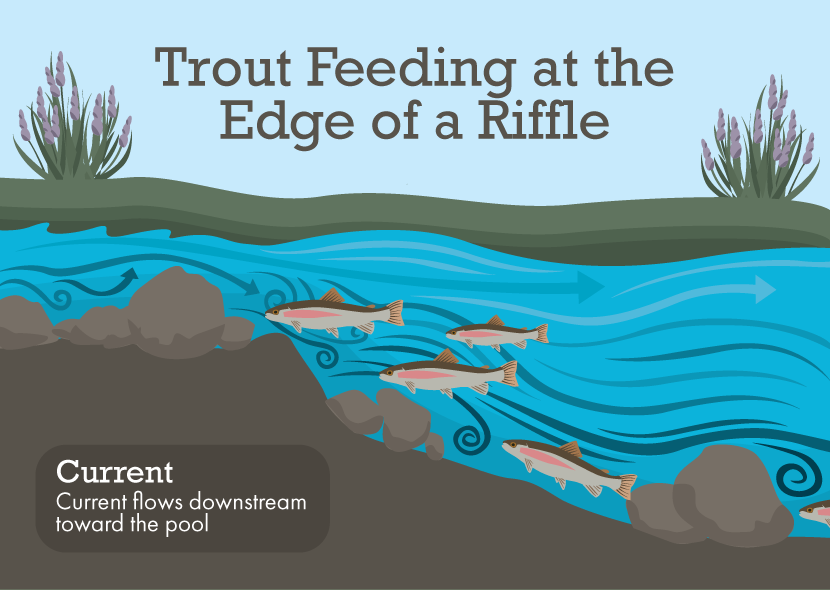

There were trout in the main currents as well, but because we were fishing a Trico hatch it was easier to spot the trout in the slow water. There is no reason to think that if we were fishing blind the trout would not have been in the same spots. Trout in rich rivers are evenly distributed, all over the place, because there is enough food to support them everywhere. Even in shallow sloughs with a mud or sand bottom, spots that look more suitable for minnows or frogs, trout can be found. In fact I’ve noticed that large brown trout in spring creeks seem to prefer these places over the deeper channels. On the other hand, in infertile rivers trout distribution is spotty. They will not be found in backwaters because it might be an hour’s wait for a piece of food to drift by, even at the height of a heavy hatch. So trout in rivers that aren’t so rich frequent the logical spots, the places that scream for a well-placed cast with an Adams or Hare’s Ear nymph. These logical places are the areas protected from the heaviest flow of water, but close enough to the main current so a sideways tip will allow trout to intercept food. At the edge of seams, at the tail of a pool, in front of and behind rocks, and where the head of the pool spills over a shelf-these are all logical places, and we’ll talk more about them in the next chapter on stream reading.

本流にも鱒はいたがTricoのハッチを釣っていたので、緩やかな流れの鱒に気づくのは簡単だった。ブラインドで釣っていたなら、同じ場所に鱒がいなかったと考える理由はない。豊かな川の鱒たちは、どこにでも十分なエサがあるので、均等に分布している。泥や砂底の狭い沼地、ミノーや変えるがいそうな場所でさえ、鱒がいるのだ。実際、スプリングクリークの大型のブラウントラウトは深い水路よりも、こういった場所を好むことに私は気が付いた。他方、不毛な川の鱒の分布は点在している。ハッチが盛んなときでも、エサが流れてくるまで1時間待つことになりかねないので、バックウォータでは鱒は見つかりません。そのため、それほど豊かでない川の鱒は論理的なスポット、つまりアダムスニンフやヘアーズイヤーニンフをうまくキャストできる場所を、頻繁にお訪れるのです。この論理的な場所は、最も激しい水流からま持たれた場所でありながら、本流に十分近く、横からのティップで鱒がエサを横取りできるような場所である。シームのエッジ、プールのテール、岩の前後、プールのヘッドが棚から溢れる場所など、これらはすべて論理的な場所で、次の「流れを読む」の章で詳しく説明します。

Applying Richness to Your Fishing Strategies

豊かさを釣りの戦略に活かす

This knowledge, then, can help you form a fishing strategy. On rich streams, cover all the water. Never assume that a trout won’t be right in front of you, and concentrate on covering the water closest to you with repeated casts, changing flies or techniques often if you aren’t getting any strikes. Armstrong’s Spring Creek offers about a mile of water on the O’Hair Ranch, and they divide it among up to fifteen fishermen a day. One fifteenth of a mile of water seems like fishing in a closet until you get around a bend where you can’t see any other fishermen and you stare at the water. If the trout are rising or it’s sunny enough to see into the water, you won’t ever want to move, unless you must stretch your legs. I’ve often wished that someone would tie me to a cattle stile and make me fish twenty feet of water on Armstrong’s. I would be a better fisherman for the ordeal, and I would not be wanting for targets.

この知識は、釣りの戦術をたてるために役に立つだろう。豊かな渓流ではすべての流れをカバーしましょう。目の前に鱒がいないと考えず、手前の水域を集中して何度もキャストし、アタリがなければフライヤ釣り方をこまめに変える。アームストロング・スプリングクリークは、オーヘアー・ランチにある約1マイルの水域で、一日最大15人の釣り客に割り当てられている。15分の1の水域は、他の釣り人がみえないくなるカーブを曲がって、水面を見るまでは、クローゼットの中で釣りをしているようです。鱒がライズしたり、水中が見えるほど晴れているなら、どうしても足を伸ばしたくないのなら、もう動きたくなるものです。私はよく、誰かが私を牛の柵に縛り付けて、アームストロングの水深20フィートを釣らせればいいのに、と思うことがある。その試練のおかげで、私はよりよい漁師になれるだろうし、ターゲットにこまることもないだろう。

Trout in infertile rivers (top) will be found in the main flow, while those in rich streams (bottom) will be found throughout the channel, even in near-stagnant sloughs.

If you tied me to one of the hemlocks along Manchester Brook, though, I’d be ready to gnaw through the rope in five minutes. On infertile rivers, pass up much of the water, the stuff that doesn’t look fishy. Move faster between spots, then concentrate hard on the bestlooking water. You can also move faster on infertile rivers because the fish don’t agonize over fly patterns — so neither should you. Trout in infertile rivers will move farther for a fly, so unerring casts are not as important here, and if your fly lands within a foot of where you think a trout is lying and floats drag-free (or swings properly if you’re fishing a wet or streamer), make a few more casts and move on. I don’t want to suggest that you get sloppy, but many times I have seen trout in unproductive streams move five feet for a dry fly. The only time a trout will move this far on a fertile river is when there are large, meaty flies like salmon flies (a huge, size 4 or 6 stonefly that hatches on western rivers) or grasshoppers on the water.

マンチェスターブルック沿いのヘルムロックの1つに私を縛り付けたら、5分でロープを噛み切って(gnaw through)しまうだろう。不毛な川では生臭く見えない、水域の大半を見送れ。スポット間の移動を速くし、最も良さそうな流れに集中する。また、不毛の川では魚がフライパターンに悩むことがないでしょうし、そうする必要のないので、より速く移動することが可能です。不毛な川の鱒はフライのために遠くまで移動するので、正確(unerring)なキャストはそれほど重要ではありません。そして、フライが鱒のいる場所から1フィート以内に着地し、ドラグフリーで浮くなら、数回キャストして、次へ進みます。だらしなくなることを勧めたくありませんが、生産性のない川で、鱒がドライフライのために5フィート移動するのを何度も見たことがあります。肥沃な川で鱒がここまで移動するのは、サーモンフライやバッタなどの肉厚のフライが水面にいるときだけです。

Remember I said I was going to give you some great excuses for getting skunked? Here’s one that relates to the richness of a trout stream: In fertile rivers trout appear to feed in spurts, with periods in between when they seem uninterested in any food and can’t be tempted with any fly. There are exceptions: although some biologists have observed these slack periods, Bob Bachman’s Spruce Creek fish never stopped feeding in the daylight hours when he could see them. Generally speaking, however, there are slack feeding periods in rich streams — not only in winter or the early season, when nobody argues with the fact that trout feed for only a couple of hours when the temperature climbs above 50 degrees, but during the height of the season, when water temperatures are perfect and insects are in the drift all day long. In streams that aren’t so rich trout feed even at high noon and in late afternoon (times when trout from richer waters most often take a siesta). Because they never get enough food, they are on the alert all the time. As we saw in the last chapter, though, trout learn to anticipate cycles of abundance, and trout in richer streams may be able to kick back for a couple of hours in the afternoon, knowing there will be a spinner fall in the evening.

坊主(get skunked)だったときの言い訳をいくつか紹介すると言ったのを覚えているだろうか?ここで、鱒川の豊かさに関連するものを1つ紹介しよう。肥沃な川では鱒は猛烈に(in spurts)エサを食べるように見えるが、その間はエサに興味がないように見え、どんなフライでも誘惑できない時期がある。例外もある。生物学者の中にはこうした弛緩期を観察する人もいるが、ボブ・バックマンのスプルース・クリークの魚は彼が見ることのできる日中の時間帯には決して採餌を止めない。しかし一般的に言えば、豊かな川には摂餌の穏やかな時期がある。気温が50F(10C)以上に上がると、鱒は2−3時間しか摂餌しないと言う事実に、誰も反論しない冬やシーズン初期だけでなく、水温が完璧で一日中虫が漂っているシーズン最盛期にもある。それほど豊かでない川では、鱒は正午や夕方(豊かな川の鱒は、昼寝をすることが多い時間帯だ)にエサを食べる。エサが足りないので、常に警戒している。前の章で見たように鱒は豊かさの数奇を予測することを学び、夕方にスピナフォールがあること知りながら、豊かな川の鱒は午後数時間くらいくつろぐ(kick back)ことができるのかもしれない。

If I’m fishing a biologically productive river like the Delaware or the Bighorn and I go without a strike for a couple of hours, I don’t brood, because I know he trout will switch on later. (This is assuming I have confidence in the fly I’ve tied on and the way I’m fishing it.) But if I fish over two pools in an infertile river without a strike, I look for another explanation. The fly I’ve chosen may be so far off that the trout won’t look at it or someone may have just fished through the pool and spooked all the fish. I may not be fishing the fly deep enough (often the case in high, cold water), or there may be no trout in these two pools. Another possibility is that I may have spooked the trout with clumsy wading and sloppy casts. In any case, if the situation arises, I either pack up and move, or sit on the bank and make adjustments to my tackle and my approach.

デラウェア川やビッグホーン川のような生物学的に生産性の高い川で釣りをしていて、数時間アタリがないとしても、私は悲しんだりしない。なぜなら、鱒は後でスイッチをいれてくれると思うからだ。(これは、タイイングしたフライトと釣り方に自身があることが前提だ)しかし、不毛な川で一度もアタリ無しに2つのプールを釣り上げなら、別の説明を探します。選んだフライが、鱒がそれを見つけることが出来ないほど遠くにあるか、誰かがプールを釣り上げたので、魚がまったく神経質になっているのかもしれない。フライを十分な深さにしないで釣っているのかもしれないし(水位が高いか、水温が低い場合に多いときに度々ある)、魚がいないのかもしれない。また、別の可能性は不器用(clumsy)なウェイデングとずさんな(sloppy))キャスティングで、鱒を怖がらせたのかもしれない。いずれにしろ、そのような状況になったら、荷物をまとめて移動するか、土手に座ってタックルと釣り方を調整する。

How Many Trout Are in That Stream?

小川にどう暗い鱒がいるか?

The number and size of trout a stream can support are always limited by something, but almost never by fishing pressure or other predation. Populations are usually limited by the physical features of the stream, and you can make predictions about how many trout a stream holds by an estimation of its richness. Infertile streams have little migration, stunted adults, and many juveniles, Rich streams, on the other hand, are space-limited. Trout can get enough food anywhere in the stream, and the total number of trout is limited by the number of available places to hold and feed without wasting an inordinate amount of energy. A rich stream with a bottom covered with rubble of different-sized rocks offers lots of nooks and crannies to break the force of the current, and it can hold many more trout than a stream of equal richness with a sand or gravel bottom. A spring creek with many weedbeds offers protection from the current and places to hide when danger threatens, and it can hold more trout than an equally rich stream that has been widened, shallowed, and trampled by cattle.

1つの小川が養える鱒の数とサイズは、常に何かによって制限されているが、釣りや他の捕獲による部分はほとんどない。通常、個体数は川の物理的な特徴で制限されていて、その豊かさを推定することで、どのくらいの鱒がいるか、予測することができます。不毛な川では回遊が少なく、成魚は発達不良で、幼魚が多くいます。他方、豊かな川にはスペースに限りがあります。鱒はかわのどこででも十分なエサを得ることができ、鱒の総数は過剰なエネルギーを消費せずにエサが得られる場所の数によって制限される。川底が大小様々な石ころで覆われた豊かな川には、水流を弱める静かな場所(nook)と岩の割れ目(cranny)があり、砂や砂利底の同じ豊かな川よりも、もっと多くの魚を養うことができる。水草のスプリング・クリークでは流れから身を守り、危険が迫ったとき身を隠す場所があり、同じように豊かな川でも、川幅が広くて浅く、牛に踏み荒らされる川よりも、多くの鱒が生息できる。

Can you spot all the trout in this photo? A spring creek offers enough food to keep all of these fish happy, even though they're in close proximity.

A food-limited stream hosts trout of many different sizes, with frequent interactions among individuals (in competition for space) and net migration downstream. This migration, usually of the largest individuals in a population, can help you find some interesting fishing on today’s crowded waters. The lower reaches of many of our richest and most famous trout streams offer fishing for big trout in water usually thought to be the home of bass, northern pike, walleyes, and even carp. These lower-river trout seldom respond to hatches, if indeed there are any in such warm-water habitats, so prospecting techniques will help you find them. I’ve explored the lower Beaverkill and Delaware in the Catskills, well out of the famous trout water, and the lower Battenkill, and I’ve found surprisingly good fishing for large brown trout. Friends tell me about equally good fishing well out of the supposed trout range on the Madison, Bighorn, and Missouri.

エサの限られた渓流では、様々な大きさの鱒が生息していて、個体間の統合(場所の奪い合い)や下流への賞味の移動が頻発に行われる。この回遊は、通常、個体群の中で最も大きな個体の回遊であり、今日の魚影のある水域で興味ある釣りに出会うことができる。最も豊かで有名な鱒川の下流では、通常バスやノーザンパイク、ウォールアイ、さらにはコイが生息していると考えられる水中で、大型のマスを釣ることができる。これらか流域の鱒はほとんどハッチに反応しないが、温水域に生息しているものがあれば、そのため、探索のテクニックで見つけることができる。キャッツキル山脈のビーバーキル川やデラウェア川の下流、有名な鱒川から離れて(well out of)、そしてバッテンキル川の下流を探ったが、大きなブラウントラウトが驚くほどよく連れたことに気づきました。マディソン川、ビッグホーン川、ミズーリ川で、鱒が生息していると思われている範囲からずーっと離れたところで、同様に良い釣りができると友人から聞いている。

Spawning conditions are poor in these places, and most of the trout ascend to the upper river to spawn, or they use a tributary stream. As you might suspect, water temperature is the main limiting factor for trout populations in these places. You can confine your search to the mouths of tributary streams, especially in the summer, and that is a relief because the lower reaches of these rivers are often huge. On one mammoth river in the Northeast (I would be risking the attention of a hit man if I used the name), there is a tightlipped group of local fishermen who fish a deep, wide stretch of water a hundred miles below what is considered by the local chamber of commerce to be trout water. At the mouth of each coldwater tributary stream is a whirlpool, and just before dark these fishermen launch float tubes into the whirlpools and slowly revolve into the sunset. In a stretch of water known for walleyes and smallmouth bass, they catch rainbows that average about twenty inches long.

これらの場所では産卵条件が悪くほとんどの鱒は上流に上って産卵するか、支流を利用する。ご推察の通り、このような場所では水温が鱒の個体数を制限する主な要因です。特に夏場は支流の河口に限定して(confine)探すことができ、これらの川の下流域は巨大であることが多いので、その点で安心です。東北地方のあるマンモス川(この名前を使うと、殺し屋に目をつけられる危険がある)では、地元の商工会議所が鱒の川とみなす100マイル下の深く広い範囲を釣る、口が堅い地元の釣り人グループがあります。冷水の支流の河口には渦があり、暗くなる前にこの釣り人たちは渦の中にフロートシューブを放ち、ゆっくりと夕日に向かって回転していく。ウォールアイやスモールマウスバスで知られる水域で、彼らは平均20インチほどのニジマスを釣り上げる。

Aquatic crustaceans like this scud, show here with an imitation, indicate rich water.

Why Are Some Streams Richer than Others?

なぜ他の渓流より豊かなのか?

Now that you know some advantages to learning to gauge richness, let’s explore the reasons for these differences in productivity. Calcium compounds, found in many sedimentary and metamorphic rocks, counteract acidity. The amount of biomass in a stream, particularly the pounds per acre of trout flesh, is directly related to the pH. The more bicarbonate in solution, the more acid is neutralized, and the higher the pH. The higher the pH, the more productive the trout stream. Calcium in solution is also suspected to benefit the physiology of trout directly. Apparently it helps the fish fight off toxins in the water. Plants can also pull a molecule of carbon dioxide directly off calcium bicarbonate in solution, so streams with high calcium content support more plant life. More plants mean more insects. And fatter trout.

さて「豊かさ」を測ることの利点が分かったので、これら生産性の違いの理由を探ってみよう。多くの堆積岩や変成岩に含まれるカルシウム化合物は、酸性度を打ち消す作用がある。河川のバイオマス量、特に1エーカー当たりの鱒の肉量は酸性度pHに直接関係している。水溶液中の重炭酸塩が多いと、酸は中和され、pHは高くなる。pHが高いほど、鱒川はより生産性が高くなる。また、水溶液中のカルシウムは鱒の生理機能に直接役に立つと考えられている。明らかにこれは魚が水中の毒素を撃退するのに役に立つ。植物は炭酸水素カルシウムの溶液から直接二酸化炭素を取り出せるので、カルシウムの含有量が多い川はより多くの植物を養うことができる。植物多くなれば、昆虫が多くなる。そして鱒も太る。

<補足:炭酸カルシウムが増えると、pHが上がる理由(酸性低下)>

まず、炭酸カルシウムが雨水や二酸化炭素を含んた水に溶解すると、炭酸水素カルシウムを生成する。つぎに、生成した炭酸水素カルシウムは石灰(Ca+)と重炭酸イオン(HCO3-)に解離。最後に、水素イオンが石灰によって土壌粒子から土壌溶液へ交換浸出。あるいは土壌溶液中の水素イオンが、重炭酸イオンと反応して溶存二酸化炭素、水と二酸化酸素(気体)へ変化。酸性の原因の水素イオンが消費されて、pHが上昇する。

The amount of calcium in a stream also determines the supply of one type of organism that is extremely valuable as a trout food — crustaceans. The outer shell of these animals is made from a compound high in calcium, and because they absorb it directly from the water, the abundance of crustaceans in a stream is directly related to the. concentration of calcium bicarbonate. Crayfish, sow bugs, and amphipods (or scuds, as fishermen call them) are a highenergy source of food year-round. These animals do not hatch out of a river as aquatic insects do, so toward the season’s end and throughout the winter, when mature insects have flown away and mated and their offspring are too small to be of much use, full-sized, adult crustaceans are available. Crustaceans are easy to capture and high in protein and fat. Wherever they are found in great numbers, you will find lots of corpulent trout. Nymph fishing is superb in streams with large populations of crustaceans, to the point where trout often ignore heavy mayfly hatches because crustaceans give them a source of high energy without the costly risk of surface feeding. The chapter on nymphs will give you some ideas on how to take advantage of this opportunity.

渓流のカルシウム量は、鱒のエサとして非常に貴重な生物(有機物)の一種である甲殻類の供給量を決定する。これらの動物の外殻はカルシウムを多く含む化合物でできており、自ら直接カルシウムを吸収するため、河川における甲殻類の数は重炭酸カルシウムの濃度と直接関係している。ザリガニ(crayfish)、ダンゴムシ(sow bugs)、両足類(漁師はスカッドと呼ぶ)は、年間を通して高エネルギー源となる植物です。これらの動物は水生昆虫のように川から羽化しないので、季節の終わりから冬にかけて、成熟した昆虫が飛び去り、交尾して、その子供が小さくてあまり役立たないとき、フルサイズの携帯の甲殻類が手に入るのです。甲殻類は捕まえやすく、高タンパク質で高脂質だ。甲殻類が大量発生している場所には、肥えた(corpulent)鱒がたくさんいいるだろう。

A Brief Field Guide to Rich and Poor Trout Streams

豊かな鱒川と不毛な鱒川への簡単なフィールドガイド

Two minerals form the bulk of freshwater buffering systems: calcite and dolomite. Calcite is pure calcium carbonate, and dolomite is mostly calcium magnesium carbonate with various impurities. Limestone is the most common source of these minerals, and the most productive trout streams in the world flow through limestone. You can spot limestone bedrock by its sedimentary layers and its brown or yellowish color. Because limestone occurs in flat layers, rocks along the banks of a river with limestone are flat plates, as opposed to the rounded igneous or metamorphic rocks of less fertile streams. Sandstone and shale, sedimentary rocks that don’t contribute much to the fertility of a stream, can be distinguished instantly from limestone or dolomite with a couple of drops of vinegar or dilute hydrochloric acid. Rocks that contain calcite or dolomite effervesce or fizz when you put the weak acid on them. Did you ever think you could predict how to fish a trout stream by carrying a vial of vinegar with you?

淡水の緩衝システムの大部分は、方解石(calcite、炭酸カルシウムに結晶)とドロマイト(dolomite)という2つに鉱物で構成されています。方解石は純粋な炭酸カルシウムで、ドロマイトは炭酸カルシウム・マグネシウムに様々な不純物が混ざったものです。石灰岩はこれらの鉱物の最も一般的な供給源であり、世界で最も生産性の高い鱒川は石灰岩の中を流れています。石灰岩の岩盤は、堆積層(sedimentary)と茶色と黄色がかった色で見分けられる(spot)ことができる。石灰岩は平坦な層で発生するので、石灰岩のある川の土手は、肥沃でない丸みを帯びた火成岩や変成岩とは対照的に、平らな板状になっている。渓流の豊かさにあまり貢献しない砂岩や頁岩(けつがん)などの堆積岩(sedimentary)は、酢や希塩酸(dilute hydrochloric acid)を数滴垂らせば、石灰岩やドロマイトと瞬時に見分けができる。方解石とドロマイトを含む岩石は、弱酸を掛けると発泡(fizz)する。酢の小瓶(vial)を持ち歩くことで、鱒釣りの方法を予測できると思ったことありませんか?

These limestone ledges along the Madison in Montana betray its richness at a glance.

Gypsum and marble also buffer trout streams and make them richer because they contain calcium carbonate. You can tell them from other whitish rocks, such as quartz, because they lack the large, crystalline grains you see in rocks that contain quartz. They also usually have a crumbly look, which comes from their solubility in the weak acid of rainwater. Marble is metamorphosed limestone or dolomite, and because of the heat and pressure it has undergone, it is not as soluble as limestone (sometimes you have to pulverize it before it will fizz with weak acid), but marble still offers strong buffering properties. The Battenkill flows through a valley flanked by insoluble granite and gneiss to the east and marble bedrock to the west. Its pH fluctuates from around 5 below tributaries or springs entering from the east to more than 7 downstream of tributaries entering from the west. Trout in the brooks on the eastern slope will take a big dry fly all day long, regardless of the insects hatching or the time of day, but if you hop over to the other side of the valley, the trout often ignore a blind-fished dry fly. You have to use smaller flies that look more like the insects that are hatching during the current week, and the trout seem to have periods of lockjaw when no fly will work. The trout in the western tribs are also bigger and fatter.

石膏(gypsum)と大理石は炭酸カルシウムを含んでいるので、鱒川を緩衝し、豊かな環境を作っています。石膏には、石英を含む岩石に見られる大きな結晶粒がないため、石英などの他の白っぽい岩石と見分ける(tell A from B)ことができる。石膏は、雨水の弱酸性に溶けるため、砕けたような外観をしているのが特徴です。大理石は石灰岩やドロマイトが変成したもので、熱と圧力を受けているため、石灰岩ほどには溶けませんが(弱酸性で発泡する前に、粉砕しなければならないこともある)、それでも大理石は強い緩衝性を持っている。バテンキル川は東側が不溶性の花崗岩(granite)や片麻岩(gneiss)、西側が大理石の岩盤に挟まれた(flank,そそり立つ)谷を流れている。東から流れ込む支流や泉の下流はpH5程度、西から流れ込む支流の下流はpH7以上と、pHの変動している。東側斜面のブルック川にいる鱒は虫の羽化や時間帯に関わりなく、一日中大型のドライフライが喰われるが、谷の反対側に飛び移ると、鱒はブラインドフィッシングのドライフライを無視することが多い。その週に羽化している虫に近い小型のフライを使う必要があり、そんなフライも効かないロックジョー(lockjaw)の時期があるようです。西側の支流の鱒はより大きく、より太っている。

Rocks composed mainly of silica contribute nothing to the productivity of a trout stream because they release no carbonates into the water. Silica rocks in streams can be recognized by their smooth, rounded shapes and crystalline structure. The ones you commonly see making up the beds of unproductive trout streams are gneiss, sandstone, quartzite, and various forms of granite.

主にシリカを含む岩は、水中に炭酸塩(carbonate)を放出しないので、鱒川の生産性に何も寄与しない。渓流のシリカ質の岩石はなめらかで丸みのある形と結晶構造で見分けることができる。生産性の低い鱒川でよく見られるものは、片麻岩(gneiss)、砂岩(sandstone)、珪岩(quartzite)、そして様々な花崗岩(granite)です。

Seldom do I predict the richness of a trout stream solely by staring at the rocks. It’s easier and more accurate to eyeball other clues in and around a stream and use the geology as one piece of the puzzle. For example, the color of the water can often be a dead giveaway to its richness. The tea-colored water so common in the north country indicates an infertile stream, where trout will be small, slow-growing, and eager to take almost any fly pattern. In the limestone belt of Pennsylvania many of the streams have a gray or white tint due to undissolved calcium carbonate, and the trout are well-fed, pickier about what nymph they take, and less inclined to come to the surface for a blind-fished dry fly. Water with no apparent color is not much of a help — it can indicate either a stream where all the brownish humic acid has been neutralized by carbonates, or, as in many high-altitude streams in the Rocky Mountains, water that has few dissolved minerals of any kind. Crystal-clear water can indicate purity, but absolutely pure water is less productive than water that contains some dissolved nutrients.

岩石を見つめるだけで、その渓流の豊かさをよそくすることはめったにない。それよりも、川の中や周辺にある他の手がかりを目視し、地質をパズルの1ピースとして使う方がより簡単でより正確です。例えば、川の水の色は豊かさの動かぬ証拠(a dead giveaway) である。北国でよく見かける茶色の流れは、鱒が小型で、成長が遅く、どんなフライパターンにも反応するような不毛な川を意味します。ペンシルベニア州の石灰岩地帯では、多くの川の水は溶け切っていない炭酸カルシウムによって灰色か白色で、鱒は良く摂餌し、どんなニンフを取るか選り好みし(pickier)、ブラインドフィッシングのドライフライにはあまり水面に出てきませんincline、〜する傾向がある)。色のない水は役立たない。褐色の腐植酸が炭酸塩(carbonate)で中和された水か、ロッキー山脈の高地の渓流のように、溶存ミネラルがほとんどない水であることを示している。透明な水は純粋であることを示すが、完全に純粋な水は溶解している栄養素を多少含んでいる水よりも生産性が低くならない。

Civilized Richness

This is a hard pill for most of us to swallow, but water polluted with human or animal waste is always more productive than pristine water. H. T. Odum, one of the world’s leading ecologists, once wrote, “Polluted streams are possibly the areas of highest primary productivity on the planet.” The Bow River in Alberta is one example. Above the city of Calgary the Bow is relatively infertile and can be easily blind-fished. Below the city, where the waste of over a million people enters the river, it is fertile beyond comparison in that part of the country, and the trout show the pickiness, reluctance to feed at certain parts of the day, and hesitance to come to the surface that are common among well-fed fish. Studies in Michigan and Pennsylvania have shown that removing domestic sewage can dramatically reduce the productivity of a trout stream, while adding it can make an infertile stream rich. The same goes for water that flows through agricultural land. Sewage and agricultural fertilizer are rich in phosphates and nitrates, and the lack of these nutrients often limits plant growth in streams, so when you add them to a stream you get the same effect as when you sprinkle 5-10-5 on your sweet corn in the spring. A study in Wisconsin found that runoff from one hectare of agricultural land puts 7.7 kilograms of nitrate per year into a trout stream. This beneficial effect walks a fine line because pollutants can also increase the biological oxygen demand of a stream, especially in hot weather, and too much organic material without cool water and a lot of riffled water can suffocate trout.

文明的な豊かさ

これはほとんどお人にとって飲み込むのが難しいが、人間や動物の排泄物(waste)で汚染された水は、自然のまま(pristine)の水よりも生産性が高い。世界的な生態学者の一人H.T.Odumはかつて、汚染された川はおそらく地上で最も基礎生産性の高い場所である、と書いている。アルバータ州のボウ川はその1つです。カルガリー市より上のボウ川は比較的不毛で、簡単にブラインドフィッシングできる。100万人を超える人々の排泄物が流れ込むその下流は国内では比較にならないほど肥沃で、鱒たちはよく肥えた魚によく見られる選り好み(pickiness)、一日のある時間帯にエサを欲しがらない(reluctance)、水面に上がってこないといった現象が見られる。ミシガン州とペンシルバニア州の研究で、生活排水(domestic sewage)を取り除くと、鱒川の生産性は劇的に低下し、逆に生活排水を加えることで不毛な鱒川を肥沃にできることが、示されています。農地に流れる水も同じです(the same goes for 〜)。

下水と農業用肥料にはリン酸塩(phosphate)と硝酸塩(nitrate)が豊富に含まれていて、これらの栄養素(nutrients)が不足すると川の植物の成長が制限される。それでこれを加えると、春にスイートコーンに5-10-5を振りかけるのと、同じ効果が得られる。ウィスコンシン州の研究では1ヘクタールの農地から流出する硝酸塩(nitrate)は、年間7.7Kgが鱒川に流出していることが示された。汚染物質は、特に暑い季節に、川の生物学的酸素要求量を増加させ、冷たい水と多くの瀬のない状態で、有機物が多すぎると鱒を窒息死させる可能性があるため、有益な効果は紙一重です。

Weeds in the water always indicate higher productivity, and as a result more invertebrates for trout to feed on. Watercress and stonewort thrive in alkaline environments rich in carbonates, and long, thin, bright green strands of filamentous algae tell you either that the water is rich in carbonates or that sewage or agricultural effluent is present. In a stream that runs through a town or city, you’ll often notice that the bottom of the river is clean above town, while below town the rocks have a coating of algae or long strands streaming from them. The water will be richer below town, as it is in the Bow, but you should be aware that not all rivers have the head of cool water to compensate for the increased oxygen demand during the summer.

You can predict the richness of surrounding trout streams by taking a shower in a nearby house or inspecting the owner’s plumbing. (You thought it was bad enough that normal people ridiculed you when you walked around in trout streams with a butterfly net. Now you’re going to be knocking on doors asking for a cup of vinegar and a look at the bathroom sink.) Calcium carbonate in the water is the same stuff that causes “lime” in your plumbing. If the local water supply contains a high concentration of carbonates, chances are the nearest trout stream does, too.

水中の雑草は常に生産性が高いことを示し、その結果、鱒のエサとなる無脊椎動物(invertebrate)の数も多くなる。クレソン(watercress)やオシベ(stonewort)は炭酸塩を多く含むアルカリ性環境で成長し、細長く鮮やかな緑色の糸状の藻類は、この水が炭酸塩を多く含むか、下水(sewage)や農業排水(agricultural effluent)があることを示す。町や都市を流れる川は、町の上流では川底はキレイで、町の下では岩は藻が付着したり、長い筋が流れていることがよくある。町下はボウのように水が豊かになりますが、すべての川が夏場の酸素需要の増加を補うために冷たい水の頭を持つわけではないことに注意が必要です。家の近くでシャワーを浴びたり、持ち主の配管(plumbing)を調べたりすることで、周辺の鱒川の豊かさを予測できます。(バタフライネットを持って鱒川を歩くことは、普通の人々から揶揄されるのが嫌だと、君は思った。こんどは酢を一杯飲ませてくれとか、風呂場を見せてくれとか、ドアを叩きまくることになるので)。水中の炭酸カルシウムは、配管の石灰化(lime)の原因となるものと、同じものです。地元の水道水に高濃度の炭酸塩が含まれている場合、最寄りの鱒川もそうである可能性がある。

Tailwaters like the South Platte can be as rich or richer than spring creeks, and the banks usually show stability, with no sign of frequent flooding.

Tailwaters Are Usually Rich, Too

I lied when I told you that spring creeks are the richest trout environments in the world. They are the richest natural trout environments. As a class tailwaters are the richest trout streams in the world, and when you think of the waters fishermen dream to wade in, you have trouble leaving out the Henry’s Fork, Madison, Bighorn, Missouri, Delaware, White, Green, South Platte, or Frying Pan. All of these rivers famous for their imposing trout and plentiful hatches are made rich by the still waters above them. Dams, if they release water from the bottom of the reservoir above them, as most of the famous ones do, stabilize both flow and temperature by being miserly with spring runoff and doling it out throughout the summer. Floods are reduced, temperature extremes are moderated, and growth is easier. Nutrients are concentrated in the impoundments behind dams. Trout also benefit in tailwaters because plankton is washed directly into the rivers and eaten by insects and crustaceans. Natural streams have little plankton because it’s hard to maintain a population if you keep getting washed downstream, so invertebrate life in tailwaters enjoys a tremendous bonanza found in few natural environments.

普通、テールウォータも豊かだ

スプリングクリークは世界で最も豊かな鱒の環境だと言ったことは嘘だ。最も豊かな自然な鱒の環境である。テールウォータは世界で最も豊かな鱒の川で、釣り人がウェーディングするとき夢見る水域はヘンリーズフォーク、マジソン、ビッグホーン、ミズーリ、でェラウェア、ホワイト、グリーン、サウスぱれっと、あるいはフライングパンを外すわけにはいかない。堂々たる鱒と豊かなハッチで有名なこれらの川はすべて上流に静かな水(湖)によって豊かになっている。ダムは、有名なダムのように貯水池の底から水を放出している場合、春の放水を控えめにし、夏の間だけ水を供給することによって、流量と気温の両方を安定させることができる。洪水は減り、極端な温度差は緩和され、生育が容易になる。

How Valuable Is Rock Flipping?

岩盤浴の価値とは?

You might be thinking I’ve left out the most obvious way of determining the richness of a river — picking up a couple of flat rocks and looking at the insects waddling madly to get away. Unless you’re prepared to set up a seine, however, and trash a couple of square feet of stream bottom to get a representative sample, and then compare this sample to other streams, I don’t think you will get a fair idea of richness from rock turning. You may miss the right part of the riffle and pick up rocks that are barren just by chance. You might be looking late in the season, when most of the larger insects have hatched and their offspring are too tiny to be noticed. Many of the insects in a river cannot be found by turning over rocks — you’ll only find the clinging and crawling species and will miss the burrowers and swimmers. Sculpins, other forage fish, and crayfish are food chain supplements, ingredients that support big trout, but you’ll seldom see them when you turn over rocks in the shallows unless you look at the place the rock was rather than what is clinging to it. Also these animals usually live in deeper water than you want to reach your arm into.

平らな石をいくつか拾って、よちよちと逃げ惑う昆虫を観察するという、川の豊かさを判断するもっとのわかりやすい方法を省いた(left out)と思われるかもしれない。でも地引網を設置して、代表的なサンプルを得るために数平方フィートの川底をゴミ箱に入れて、そして各川のサンプルを比較しないなら、岩石回転から豊かさを正しく把握することはできないと思う。瀬の正しい部分を見逃し、偶然に不毛(barren)な岩を拾ってしまうかもしれません。また、季節の変わり目で、大きな昆虫が浮化して、その子供(offspring)が小さくて見えないこともある。川にいる虫の多くは、岩をひっくり返しても見つけることは出来ない。しがみついたり(clinging)はったりする(crawling)ものしか見つからず、あな蔵や泳ぐ種を見逃してしまうからだ。カジカ、他の餌魚、ザリガニは植物連鎖を補い、大きな鱒を支える材料(ingredient)ですが、浅瀬の岩をひっくり返しても、岩にしがみついているものよりも、岩があった場所に目を向けないと、めったに見ることは出来ない。また、これらの動物は通常、腕を伸ばしたくなるような深い水の中に澄んでいる。

Looking at rocks helps you pick a nymph pattern, particularly in richer streams where the pattern choice may be important, and although it can give you a hint at a river’s diversity, diversity is not as important as richness when it comes to working out a fishing strategy. Gauging the richness of a river is like “pre-stream reading”: a way of looking at the river as a whole system before you start gazing at current patterns and rocks.